Silk Making in Early Bethlehem

Part of my fascination with the early Moravians is that we are constantly learning new things about them. For example, who would have guessed they were into silk making? Or that it all began in the attic of the Single Brothers’ House.

The History of Silk

Empress Leizu aka “The Goddess of Silk“

According to legend, the story of silk began 5,000 years ago in a garden in China when a silkworm cocoon fell into an empress’s cup of tea. She noticed the cocoon starting to unravel and decided to try weaving the threads, and that’s how silk was born. Empress Leizu is still revered in China where she is known as “The Goddess of Silk” or Silkworm Mother (which doesn’t sound nearly as glamorous).

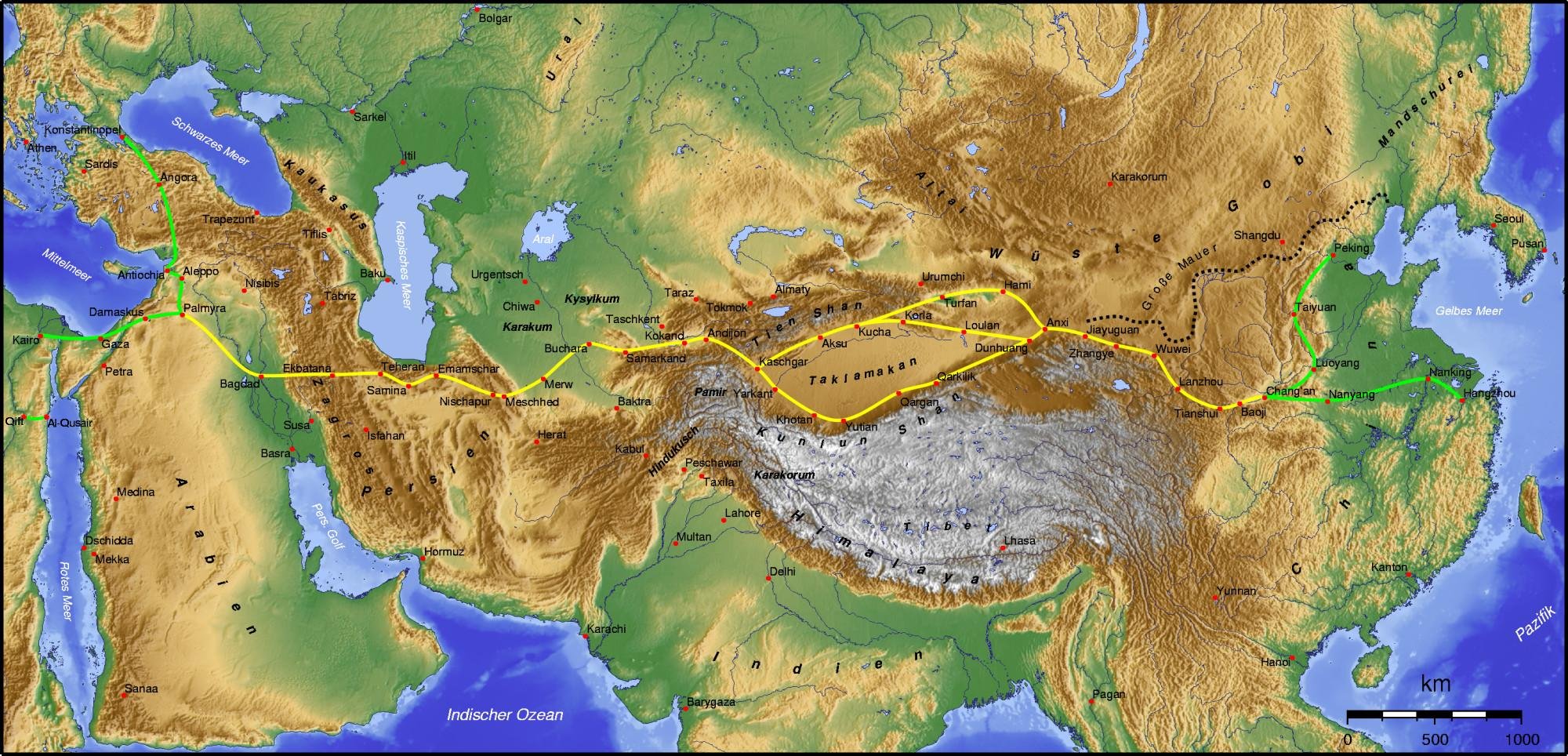

The famous trade route linking China with the west was named the Silk Road in honor of its most lucrative commodity. Nearly 4,000 miles long and used for 1500 years, the Silk Road triggered a European fascination with silk, and by the 9th century, Europe had developed its own silk industry.

The British monarch James I even sent silkworm eggs and mulberry seeds to Jamestown (which by the way was named for him). However, early efforts at growing silkworms failed., and it wasn’t until the early 1750’s that silk making started to take hold in the southern colonies.

Map of the Silk Road

Attribution: By Kelvin Case - File:Seidenstrasse_GMT.jpg revision., CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=10536100

Silk in Early Bethlehem

Philipp Christian Bader, a Moravian clergyman

Around that same time, in 1752, a Moravian clergyman named Philipp Christian Bader had silk on his mind, too. Brother Bader had noted the red mulberry trees growing wild all around Bethlehem, and he knew mulberry leaves were the only food persnickety silkworms would eat. In fact, silkworms must have been in the vicinity for a long time because the original inhabitants, the Lenni Lenape, had named the area Nolamatink which roughly translates as “where the silk worms spin.”

With dreams of creating a silk making industry, Brother Bader began experimenting in the attic of the Single Brothers’ House. Unfortunately, his efforts with red mulberry leaves and local silkworms failed; however, Brother Bader refused to give up. He imported domestic silkworms and white mulberry trees, which proved to be the magic combination. Brother Bader was called to another Moravian mission and had to leave Bethlehem, but other Brothers kept up the effort and produced nearly 20 pounds of silk in the first year.

The Life of a Silk Worm

The diagram above depicts the very short life of a silk worm, only 45-55 days. A newly born silkworm sheds (molts) its skin multiple times as it grows. Then, the ripe silkworm begins to spin a cocoon, which is made from hardened silkworm saliva and takes about three days to complete. Inside the cocoon, the silkworm transforms from a larva to a pupa and eventually emerges as a moth. Sadly, an adult moth has no mouth and must survive solely on stored body fats and fluids. The adult moths mate, females lay eggs, and then they die.

The Silk Making Process

The Cocoonery

The original cocoonery in the attic of the Single Brothers’ House would have looked something like this with a barrel filled with fresh mulberry leaves to feed the always hungry silkworms. The temperature and humidity also had to be just right, but with good care and round-the-clock feedings, after several weeks, the silkworms would begin to spin.

After about a week, the Brothers would boil the cocoons to kill the pupa and then set them out to dry. Once the cocoons were fully dry, the unwinding process could begin. Unwinding a silk cocoon requires finding the one true thread in order to unravel it as one continuous piece. Amazingly, one cocoon can provide a thread 3,000 feet long (twice the height of the Empire State Building).

Boiling and drying the cocoons

Silk Products

Silk making involved the entire community. In the next phase, the Single Brothers delivered the silk thread to the Single Sisters who would reel the slender tendrils onto a spool and spin the thread into yarn. Next, the yarn traveled to the Dye House in the Industrial Quarter, and finally, the resulting colorful yarns would be returned to the Single Sisters to transform them into needlework, ribbons, and pieces of clothing.

By the 1770’s, silk products were being sold to both locals and visitors at Horsfield House, Bethlehem’s first store, and also in the Sisters’ seamstress shop at the Single Sisters’ House. I’ve been told our very own Liesl Boeckel sometimes worked in the seamstress shop selling goods, and legend has it George Washington once stopped by the shop and bought a pair of silk stockings for his wife Martha!

Despite all this effort, Bethlehem silk tended to be of low quality. Coupled with a relatively high price tag, the local silk industry never fulfilled Brother Bader’s dream of becoming a global export..

Mulberry Mania in the 1820’s

Attribution: Jean-Pol GRANDMONT, CC BY 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Much like Tulip Fever that gripped Holland in the 1600’s, the discovery of a new variety of white mulberry tree, the Morus muticaluis, created Mulberry Mania in Pennsylvania. Local investors were taken in by an unscrupulous businessman named Samuel Whitmarsh who promoted the new variety by promising more silk at less cost—an easy path to riches. The new variety became so popular it created a speculative bubble and sold for as much as $450 a tree! However, the new trees never lived up to the hype, the bubble burst, and many in Bethlehem were left penniless.

The nefarious “Mulberry Tree Scam” ended silk cultivation for a time, but Bethlehem’s story of silk was far from over. Industrialization resulted in technologies capable of producing silk products faster than ever before, and by the 1920s, Bethlehem had become one of the world’s leading producers of silk.

To Learn More

To explore the complete story of Bethlehem silk, visit the special exhibition Unspun Silk: Stories of Silk featuring three Bethlehem sites: the Moravian Museum, The Kemerer Decorative Arts Museum, and the National Museum of Industrial History:

Historic Bethlehem Unspun Silk Exhibition

For more information about silkworms, check out this article that even explains how to grow them yourselves: